Whole and Holy

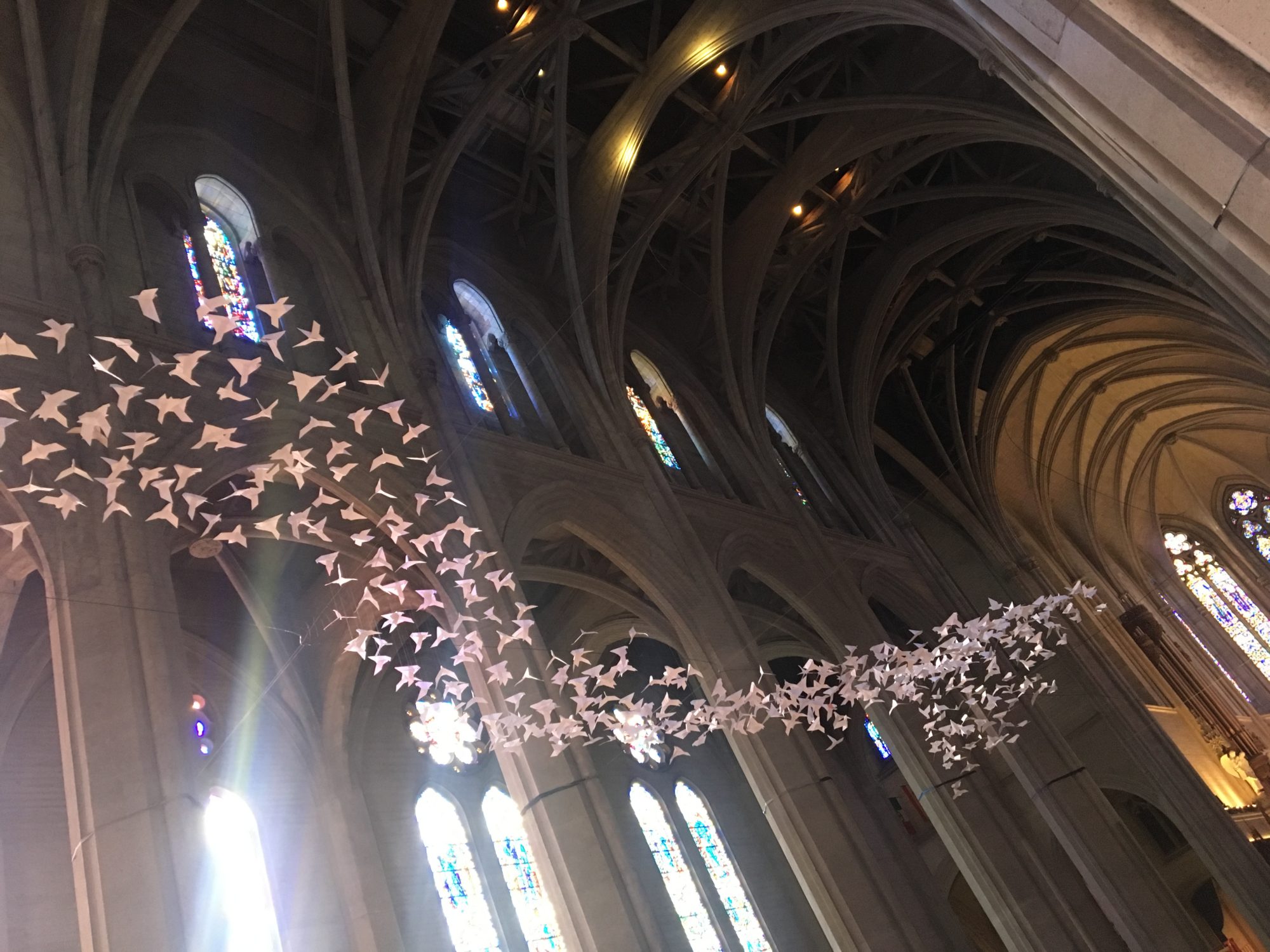

A sermon preached at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 (The First Sunday After Christmas Day)

Readings: Isaiah 61:10-62:3; Psalm 147; Galatians 3:23-25, 4:4-7; John 1:1-18

For audio, listen here

On Christmas Day, while recovering from the joyful exhaustion that was my first Christmas with you at Grace Cathedral, I watched the Christmas special of the BBC series, Call the Midwife. If it’s not a show you’re familiar with, I highly recommend it. Based on a true story, it tells the tale of the sisters of St. Raymond Nonnatus, an order of Anglican nuns working as nurses and midwives in London’s East End in the 1960s. These sisters work tirelessly in their community to deliver thousands of babies, often in circumstances only marginally preferable to a Bethlehem stable – and manage to make Anglicanism look really good while they do it. The series is poignant and funny, tender and profound – a testament to the holy realness of human life and the extraordinary power of ordinary acts of compassion. In its unflinching portrayal of the messy, risky, sometimes heartbreaking process of childbirth, the series bears witness to the truth that we are celebrating these twelve days of Christmas: that, against all odds, God comes to dwell among us as a baby, in human flesh and blood.

What Call the Midwife manages to do so brilliantly is draw attention to the holy complexity of being human: our flesh is, at once, perilously fragile and unimaginably precious; painfully broken and mysteriously whole; too often neglected and supremely worthy of care. With unusual clarity for a TV show, it tells the story of God’s grace showing up in unexpected places, mediated, not through words or doctrine, but through embodied acts of love. It is into this messy, vulnerable, joyful business of embodied life that God comes to meet us, not as a distant observer, but as one of us. The Word was made Flesh and dwelt among us.

God so loved the world, God so loved us and our flesh, that God chose to come and live as one of us in a human body. An actual body just like ours – a body with skin and organs, a body that breathed and cried and got hungry, a body that felt pain and experienced the adrenaline surge of excitement. There are other ways God could have elected to be with us – yet God chose this one. God chose human flesh. God went all in.

In church, we talk about the Incarnation a lot, we recite in the Creed every week that God “became incarnate from the Virgin Mary and was made human.” But do we hold the good news of the Incarnation at a safe distance, keeping it as an interesting but abstract theological concept? Or do we let the God who met us in the holy immediacy of a specific human body communicate the good news to our own flesh, with all its unique stories, needs, and longings?

Here at Grace Cathedral, we have spent the past year living into the theme of Truth. In 2019, we will shift our attention to a specific kind of truth – an often uncomfortable truth – as we transition into observing the Year of the Body. And these 12 Days of Christmas are the perfect time to introduce it. As I have excitedly told friends and family members that Grace Cathedral will be devoting an entire year to deliberate reflection on embodiment, their reactions have ranged from polite shock to outright horror. Many responded with something like, “Really? You’re going to talk about bodies? IN CHURCH!? Is that even allowed?” Their reactions are telling.

Generally speaking, the more uncomfortable something makes us, the more we need to talk about it. Truth telling is an uncomfortable business. And the truth is, the subject of human bodies is littered with taboos – perfectly normal parts of being human that we talk about only in code, things we don’t talk about in polite company, and certainly not in church. The result is too often deep, paralyzing shame – and a divided life, where we’re constantly hiding the parts of ourselves we’ve deemed unacceptable, keeping them outside these walls. So, in 2019, we are breaking the taboo and shining the light of God’s truth on the messy, holy reality of our own embodiment. Not to be trendy or provocative, but because God broke the ultimate taboo by having a body and being a body. We’re only following in God’s footsteps.

So what truth about human bodies did God reveal when the Word became flesh and dwelt among us? The truth of the baby in the manger is really quite simple: our own flesh – our imperfect, fragile, beautiful, holy flesh – is loved and lovable RIGHT NOW. Regardless of what illnesses and diagnoses assail us, what scars mark us, or how betrayed we feel by our bodies. God takes on, not just any flesh, but the flesh of an infant refugee in occupied territory to show us, once and for all, that bodies matter, and that all bodies are holy in God’s eyes – immigrant bodies, trans bodies, women’s bodies, aging bodies, incarcerated bodies. God is not afraid of the mess and imperfections of embodiment. Which then begs the question – why are we?

The Word is made flesh to remind us that we don’t have to be perfect to be loved. We don’t have to wait to get it right for God to meet us, and heal us, and forgive us. By taking on a human body, God shows us that there is no aspect of our humanity that God is not willing to share. That no secret pocket of shame or fear is too much for God to handle, that no brokenness is too great for God to heal, that there is nothing we need to hold back from God for fear of being ridiculed, judged, or punished. The Word became flesh to heal our deeply fractured relationship with our own bodies, so that we might be whole and holy, so that we might have the abundant life that God promises us.

Honoring the divine wholeness of our flesh is never an easy or perfect process, though it’s easy to paint an overly rosy picture of what this looks like in real life. Think of how easy it is to idolize and sanitize the manger scene – when, in reality, it was probably crowded, smelly, and full of the awkward realness of bodies colliding in close quarters. A terrified mother, going into labor with her first child in a strange city, without secure lodgings, with no extended family to support her. And then, just hours after giving birth, offering hospitality to a strange parade of shepherds, sheep, and exotic kings – in a stable that wasn’t hers, when probably all she wanted to do was sleep. Purity laws around women’s postpartum bodies are shattered; bodies of wildly different backgrounds and classes stand shoulder to shoulder with blatant disregard for social norms. There is nothing neat, tidy, or particularly respectable about the birth of Jesus, but there is a wild wholeness and an astonishing holiness. In Bethlehem, the whole, messy reality of human flesh is on full display, no holds barred – and God makes a home right there in the middle of it.

The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us. What would it look like for us to celebrate that truth in our own flesh? To imagine that Christ came, not just to save our souls at a far off judgement day, but to communicate God’s radical, unconditional love to our bodies in this life, right now? What would our healthcare system look like if we really believed that every human body was worthy of healing and care? What would our immigration system look like if we believed that no human body can be labeled as illegal, deportable, or expendable? What would our lives look like if we treated all human flesh with the same respect and dignity that we treat the bread and wine of the Eucharist?

Because the thing is, the Word wasn’t just made flesh once, 2000 years ago in a manger in Bethlehem. The Word is constantly being made flesh, every moment of every day. In our bodies. At this altar. And in this body that is us, this community, the Body of Christ. So as we celebrate this season of Christmas and as we cross the threshold into this Year of the Body, may we remember that the radical invitation of the Incarnation is always open to us: to allow God’s grace and truth to meet us in our own flesh. To recognize the wholeness and holiness of our bodies. The Word is made flesh and dwells among us. What if we really allowed ourselves to believe it?

Leave a Reply